Climate Change

Steve Mitnick has authored four books on the economics, history, and people of the utilities industries. While in the consulting practice leadership of McKinsey & Co. and Marsh & McLennan, he advised utility leaders. He led a transmission development company and was a New York Governor’s chief energy advisor. Mitnick was an expert witness appearing before utility regulatory commissions of six states, D.C., FERC, and in Canada, and taught microeconomics, macroeconomics, and statistics at Georgetown University.

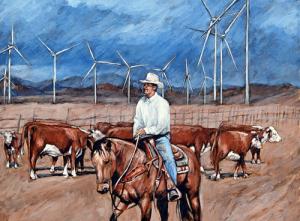

There has never been so great a threat to the grid as the threat to the globe of climate change. That the effects are gradual over decades, and imperceptible most days, and inconsistent across the myriad interfaces of nature and man, impairs our resolve to act.

Were the effects like in the 2004 flick, The Day After Tomorrow, with a tsunami covering Manhattan, whoever would be left would have no doubts and no qualms about the most aggressive climate change plans. Fortunately, the drama of climate change is less dramatic. But that just means that climate change's call to us to act, decisively so, is deceptively less than clarion.

The effects are nowhere as clear as in that film. Yet, and here's the crux of the matter, the costs, the disruptions, and the risks of forestalling the effects are quite clear.

One can for instance propose a transmission project crossing states to enable thousands of megawatts of clean generation capacity. We all know what happens next. The conversation immediately turns to its expense, its community opposition, and alternatives real and imagined. The talk about its role countering climate change is inevitably drowned out (pun intended).

As if we have all the time in the world. As if it is acceptable, indeed as if it is completely without consequence, that the time from the drawing board to grid interconnection for such a project is rarely less than a decade. And whenever the time is less than a decade, a rarity, it is so by precious little.

The origin of the problem can be found during the Richard Nixon Administration over a half century ago. A growing environmental movement wanted to slow down large industrial projects to give opponents the time and a deliberate process to examine and expose their potential effects. The National Environmental Policy Act was born and with it the Environmental Impact Statement that is now required for a far broader range of projects than anyone envisioned in 1970.

The sad irony is this. Twenty-first century projects to diminish the environmental harm of climate change are often prevented by a twentieth century process to defeat environmentally harmful projects. Talk about unintended consequences.

Often lost in this litigious process, the proportions that are involved. A project might endure years of delay, all because a few property owners perceive that they would lose some environmental quality. While that delay — let alone the probability that the project developers will ultimately just give up — effectively allows a considerable quantity of climate change gases to be emitted, that the project would have avoided, affecting us all.

Republicans and Democrats in the Congress and the Administration too are united, a particularly rare condition these days, wanting to enact reforms to this process, to enable more projects to be permitted. And more expeditiously as well. It has emerged as a top priority in Washington. Giving hope to all those that have a sense of urgency about slowing down the oncoming train of a changing climate.