Mobility Services and Electrification's Pace, Shape

Jürgen Weiss is a principal in The Brattle Group’s Boston office, where he spearheads the firm’s electrification initiatives. He is an energy economist with 20 years of consulting experience, advising clients in North America, Europe, and the Middle East.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts electrification of transport will be a slow process of turning over individually-owned vehicle stock. By 2050, it projects roughly seventeen million battery electric vehicles that are cars and light trucks. It projects twenty-three million hybrid vehicles. Together, those figures represent six percent and eight percent, respectively, of an estimated light duty vehicle stock of almost three hundred million.

Other forecasts of EV sales are significantly more optimistic, but are still largely based on a paradigm of individual car owners swapping out existing cars for EVs over time. There are many signs that the barriers to individual EV adoption are coming down with more models on the road, more range, more charging infrastructure, and lower sticker prices. These trends are also accompanied by the rapid growth of mobility services such as Uber, Lyft, and Zipcar.

The emergence of mobility as a service means there will be a potential shift of miles traveled in individually-owned vehicles to those provided by mobility service providers. Over time, this may also reduce the number of individually-owned cars.

If mobility service providers electrify their fleets more rapidly than individual car owners, a shift to mobility services creates the possibility that transport itself will become electrified a lot faster than the vehicle stock itself.

This has important implications: electricity sales growth may pick up speed sooner than currently expected, with corresponding needs to expand the clean power supply and associated transmission infrastructure.

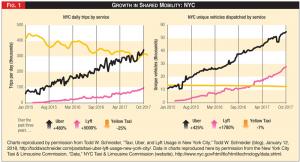

Figure 1 - Growth in Shared Mobility: NYC

Figure 1 - Growth in Shared Mobility: NYC

Also, if the growth in electrified transport comes from mobility service providers, the demands for charging infrastructure and the time pattern and speed of charging may be quite different from home- and work-based charging of a large fleet of relatively sparsely-used individually owned vehicles. This could mean that utilities have to be proactive in understanding those differences.

There are several reasons why mobility service providers are likely to electrify their fleets more rapidly than individual car owners. Unlike individual car owners, who care a lot about car attributes that have little to do with economics, fleet operators will tend to make car purchasing decisions based on total ownership costs.

The ownership cost of EVs relative to internal combustion engine cars improves the more a vehicle is used, since EVs have fewer moving parts than ICE cars. That feature lowers maintenance, and the still higher purchase price can be amortized over more miles. This means that to fleet operators EVs will be economically attractive before they are attractive to typical individual car buyers.

Two other significant barriers to EV adoption for individual car buyers - range anxiety and access to charging infrastructure - are substantially less relevant for mobility service providers. Mobility service fleet vehicles won't typically need to be able to make the rare very long trip for which electric range matters.

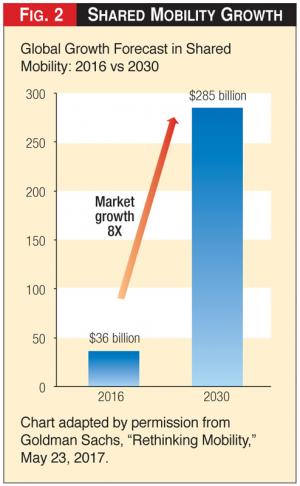

Figure 2 - Shared Mobility Growth

Figure 2 - Shared Mobility Growth

Rather, these vehicles travel relatively short distances easily covered by the one to two-hundred-mile range of the EVs already on the market today. Finally, even if the range of a shared mobility EV is not sufficient to meet daily driving needs, fleet operators of such vehicles can more easily arrange for charging infrastructure to be available.

Fleet operators can provide a relatively large, stable, and predictable charging demand. That means they can self-supply charging infrastructure. Or they can convince utilities or third-party charging infrastructure providers to supply charging services to dedicated areas such as shared mobility charging hubs.

For all of the above reasons, it seems plausible that mobility service fleets will electrify rapidly. For example, Lyft has announced that they want to expand their pilot program offering fully-electric Chevy Bolts to their drivers in their original cities, San Francisco and Los Angeles. They want to expand to new cities as well.

Rapid growth of mobility services could therefore imply that electrically-driven miles will grow quickly, much more quickly than the projections of EV adoption by EIA or even implied by more optimistic EV adoption forecasts.

Mobility services are indeed growing rapidly. In May 2017, Goldman Sachs projected that globally, ride-hailing could grow eight-fold to two hundred eighty-five billion in revenues per year by 2030, more than five times the size of the global taxi industry.

In just a two-year period between 2015 and 2017, daily trips on Uber and Lyft in New York City jumped from about fifty thousand to about four hundred fifty thousand, a nine-fold increase. Daily yellow taxi trips declined from four hundred thousand to about three hundred thousand.

See Figure One.

The rapid evolution of personal transport in New York City provides two important lessons for the potential size and speed of electrification of personal transport more broadly. New mobility options are being adopted very quickly, perhaps more in line with the speed of adoption of smart phones or social media than of household appliances or other hardware innovations. And more convenient or cheaper mobility solutions create more demand.

The latter point is striking. Over those same two years, the total number of trips in either a yellow taxi or via Uber/Lyft increased from four hundred thousand to roughly seven hundred thousand, or more than seventy-five percent.

If this trend continues and if mobility service companies (and potentially taxi companies) will indeed electrify their fleets relatively quickly, the implications for electric utilities, both in terms of changes to demand and to requirements for infrastructure, would be significant.

Yet, even though the increase in revenue from ridesharing is projected to be large, there are legitimate reasons to question whether recent growth rates can continue in cities that have already seen the emergence of the likes of Lyft and Uber.

See Figure Two.

Also, cities like New York, San Francisco, or Boston may not be representative of demand for shared mobility services in other cities, where individual car ownership is substantially higher, and parking is less of a problem.

However, another rapidly-approaching potential disruption could fuel an even more fundamental shift to accelerate the move towards mobility services. Fully autonomous vehicles are expected to be commercially introduced by 2020 or 2021. GM just announced that it will have its first car without a steering wheel on the road by 2019 - next year! Both Lyft and Uber are advancing projects to offer autonomous rides to their customers.

Lyft, for example, began offering rides in AVs in partnership with NuTonomy in Boston in late 2017.

There was still a driver to jump in when needed. Lyft was offering rides in AVs at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas in January 2018. Uber's efforts to test AVs on the streets of Pittsburgh are well documented.

In November 2017, Uber ordered 24,000 AVs from Volvo, a sign that a broader roll-out of AVs is already underway. Uber is expecting autonomous taxis to appear on the streets as early as next year, 2019. While it is likely that the first AVs used by ride sharing companies will still have a driver, clearly the drivers will disappear over time, at which point the cost of riding in such a vehicle will decline substantially.

AVs could lead to a much more fundamental change in how and when we use cars and whether or not we continue to own cars, electric or not. At that point, it seems at least plausible that owning multiple cars will no longer make sense for many two- or more vehicle households. That would signal a much more significant shift of vehicle miles traveled from our own cars to shared rides on fleet operated, autonomous EVs.

It is of course possible that many individual car buyers will wait another car purchase or two before they are confident enough to buy an EV or jump into an Uber/Lyft, with or without driver. Consequently, the electrification of transport via a move from individualized transport to shared mobility services will be more gradual and/or less pronounced than described here.

However, the scenario outlined here is a real possibility. Most major car companies have invested heavily in mobility services, directly or indirectly. GM created its own mobility service subsidiary, Maven, and also invested five hundred million dollars in Lyft.

Toyota invested in Uber and VW in Gett, an Israeli based ride-sharing app. Daimler and BMW invested heavily in their own shared mobility platforms, car2go and DriveNow, respectively. And the list goes on.

A more rapid electrification of transport along these lines is significant for utilities in at least two ways.

First, more rapid electrification of transportation could lead to stronger sales growth earlier and in the long run. This would potentially be coupled with an increase in miles traveled as a consequence of the declining costs of shared mobility services.

This could have implications for how rapidly the generation and transmission system will have to grow and adapt relative to the current paradigm of slow or no growth. Policy, economics and consumer and corporate attitudes increasingly favor renewable power sources. That may mean that the pace of adding renewable generation sources and transmission to bring them to market will have to quicken. Both to replace existing fossil generation resources and to accommodate the growth in demand from electrifying transport.

Second, electrification of transport likely also means very different demands for the location, speed, and timing of EV charging, driven by replacing miles traveled in individually-owned vehicles with miles traveled on mobility service fleets.

Individually-owned EVs imply a lot of home and workplace charging with relatively modest demands for charging speed. That's because the average individually owned EV only needs to drive about thirty miles a day and sits idle for long periods of time at home or at the work place. By contrast, mobility service fleet vehicles, especially autonomous ones, will likely travel many more miles per day and may need to be "topped up" with fast charging throughout the day to be continuously available for rides.

There are also reasons to believe that once mobility fleets become autonomous, other service functions such as cleaning will need to be performed in central locations. It is plausible that at least some of the charging demand from these fleets will be for more frequent rapid charging of multiple vehicles at "charging/servicing hubs" throughout the day.

Since the charging loads would be more concentrated and the demand would come from a smaller number of individual customers (the mobility fleet owners/operators), making sure the required infrastructure is in place may actually be easier for utilities.

Easier than ensuring a distribution grid that is prepared for any number of individual car owners buying any number of EVs and charging them at various speeds.

However, the resulting charging demand could be much higher and concentrated in certain locations, requiring utilities to ensure they are ready to accommodate significant increases in charging demands during various times of the day. That will be likely in central business districts near the demand for shared rides. This may also have a significant impact on the size and shape of load shape they need to forecast and manage.

The move to electrified transport via mobility service providers creates the potential for significant new growth for electric utilities, a faster path to decarbonization of our economy, and significantly-enhanced mobility options for everyone.

It is therefore important that utilities keep track of the fast-paced developments in the area of mobility services and adjust their forecasting, planning and service offerings accordingly.