Jeremiah D. Lambert, a lawyer in Washington, D.C., has served PJM and other clients in the electric utility industry and has written extensively on energy-related topics.

Samuel Insull, David Lillienthal, Don Hodel, Paul Joskow, Ken Lay, Amory Lovins, Jim Rogers

As a lawyer in Washington, D.C., I have worked for many energy clients over the years. Immersed in legal detail, I felt the need for a grand retrospective view of the industry, particularly its electric utility core, that had absorbed so much professional effort during my career.

I envisioned a history, not a technical monograph, built around the careers of seven movers and shakers from the industry's origins in the nineteenth century to the present. I wanted to capture the complex interplay between private investor-owned utilities and government regulation that has shaped the industry in the United States.

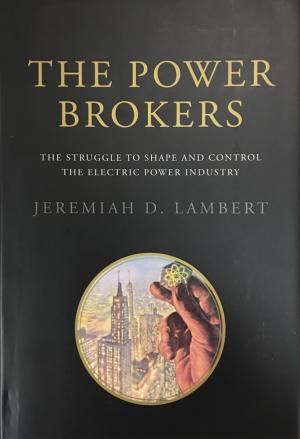

At the same time, to attract a broader audience, I sought to craft a narrative, telling the story of an essential bedrock business through the players who influenced its course. I titled the book, "The Power Brokers," to reflect its political and technical implications.

Finding a mainstream publisher was itself a quest. After a period of trial and error, I engaged the interest of MIT Press, a leading academic publisher, which saw the virtue of my book as a history of technology.

But not before farming out my manuscript to anonymous peer review readers, who read it at their leisure and discretion. When their verdict proved favorable, I was greatly relieved. Book review in the groves of academe is not for the faint-hearted.

Insull

“I sought to craft a narrative, telling the story of an essential bedrock business through the players who influenced its course.” – Jeremiah D. Lambert

“I sought to craft a narrative, telling the story of an essential bedrock business through the players who influenced its course.” – Jeremiah D. Lambert

The book's first power broker was Samuel Insull, the founding architect of the nation's electric power business, whose imprint is still visible today.

A supremely ambitious immigrant from England, as a young man Insull became Thomas Edison's right-hand aide and protégé. He promoted Edison's central station electric business, and was present at the creation of General Electric, leaving to plunge into the disorderly and chaotic infant electric utility marketplace of late nineteenth century Chicago.

Insull's imperative was consolidation and monopoly control, gained by acquiring vulnerable local competitors. "The best service at the lowest possible price," he said, "can only be obtained ... by exclusive control of a given territory being placed in the hands of one undertaking."

Insull feared rapacious and corrupt municipal politicians, who determined rates and dispensed utility franchises. He wanted instead to deal with a single benign state agency, and called for state regulation of privately owned utility monopolies.

“The Power Brokers: The Struggle to Shape and Control the Electric Power Industry,” Jeremiah D. Lambert, MIT Press, 2015.

“The Power Brokers: The Struggle to Shape and Control the Electric Power Industry,” Jeremiah D. Lambert, MIT Press, 2015.

Regulation meant protection from competition and a reliable return on invested capital. State commissions embedded exclusive utility franchises, but they did not regulate wholesale interstate transactions.

Insull built a nationwide utility holding company empire in a regulatory vacuum, driven by advanced technology, ever-lower electricity rates, new methods of finance, and towering personal ego. He overreached, made powerful enemies, and suffered a historic downfall.

President Roosevelt's New Deal attacked Insull's signature utility holding company empire by legislative fiat and used government monopolies to compete with and rein in their investor-owned counterparts. The Tennessee Valley Authority, TVA, became the government's chosen instrument in the competitive struggle that ensued.

Lilienthal

The book's second power broker was David Lilienthal, initially a director and then chairman of TVA, who proved indispensable to its survival and early success.

A whip-smart, politically connected lawyer, Lilienthal needed a market for TVA's hydroelectric power. Like Insull, he wanted to drive down rates to increase consumption and sell power to farmers and small users, neglected by the private market.

Lilienthal viewed the power industry's refusal to lower rates as a bar to electrification of the Tennessee Valley. He engaged Wendell Willkie's Commonwealth & Southern Corporation in an epic struggle for market control, pulling every political lever at his command, up to President Roosevelt, to pry business from Willkie's firm and establish TVA as a viable competitor.

At every stage of its early development, TVA was under siege from private industry, jealous members of Congress, a domineering Secretary of the Interior, and a rogue chairman. Lilienthal managed to outflank and deflect them all, but ultimately presided over an institution that closely resembled the private utilities it was designed to replace.

Hodel

TVA was not the only arrow in President Roosevelt's public power quiver. Roosevelt intended Bonneville Power Administration, BPA, to serve the same purpose for the Pacific Northwest, unlocking the low-cost power potential of the Columbia River.

Unlike TVA, however, BPA was not a free-standing government utility. It was instead a marketing agency for hydroelectric power from dams built by the Corps of Engineers. BPA could not generate its own power, and remained under the thumb of the Secretary of the Interior. In the 1970's, under the book's third power broker, Don Hodel, BPA foresaw a power shortage and embarked on an ill-considered nuclear power program, using the Washington Public Power Supply System, WPPSS, as a surrogate.

Two dysfunctional command-and-control government bureaucracies, one federal and the other local, then interacted to mount a disastrous multi-project undertaking. It was financed by WPPSS municipal bonds sold to small investors in much the same way as Insull had sold holding company securities to clerks, foremen, and company employees years before.

Under Hodel, BPA ignored warnings that the expected power shortage was a mirage. He coerced WPPSS utility members to participate.

The program went spectacularly awry. Only one of five planned nuclear plants reached completion. The others had to be abandoned and scrapped. WPPSS defaulted on bonds it had issued, imposing huge losses on bondholders and ratepayers. Top-down monopoly control revealed the arrogance of overweening managerial ambition and the absence of grass-roots and competitive constraints.

Joskow

The book's chosen protagonists were not all business lions. They also include several thought leaders, notably Paul Joskow, the book's fourth power broker. In the 1980's, as a rising and influential free-market MIT economist, he questioned Insull's industry paradigm - vertically integrated and legally sanctioned utility monopolies operating remote large-scale power stations and long transmission lines.

Among other critics, Joskow attacked the industry's inefficiency, high administered prices, and failed nuclear projects. While transmission and distribution of power remained natural monopolies, he viewed generation of power as ripe for competition. He envisioned a restructured model in which customers could bid for electricity from competitive suppliers and have it transported at fair rates over high-voltage transmission lines free from monopoly control.

An independent operator would run the lines and make a competitive real-time and day-ahead power market at marginal cost. Joskow embodied these concepts in a breakthrough 1983 book, "Markets for Power," anticipating by more than a decade the changes that reshaped much of the nation's utility industry, first in California and then federally.

But Joskow was not a Pollyanna. He foresaw many of the practical difficulties restructuring would entail.

Making his blueprint work, he cautioned, would require an exercise of industry smarts, sound oversight, and political will, none of which was in evidence as the badly designed and easily manipulated California market imploded at the turn of the century. Ultimately Joskow's vision gained traction, at PJM and elsewhere, as an alternative to command-and-control price regulation.

Lay

The restructured utility marketplace, particularly California's, drew the interest of entrepreneurs. They saw a golden opportunity to extract outsize profits by gaming poorly conceived electricity networks.

Foremost among these was Ken Lay, CEO of Enron, the book's fifth power broker. Lay consolidated prosaic gas pipelines and repurposed the resulting enterprise as a new-age energy company.

To Lay, traditional vertically integrated electric utilities were dinosaurs. He sought to exploit deregulating gas and electricity markets through Internet-based trading, capturing a sizable fraction of the nation's activity in these commodities.

All the while, Lay remained intently focused on restrictive regulation and the indispensable need for political patronage to overcome it. As Enron grew, so did his involvement in politics. A prolific Republican Party contributor, he used his influence with well-placed political allies to extract favorable rulings from FERC, the SEC and the CFTC.

"We believe in markets," Lay said. But judged by its behavior in California and elsewhere, Enron really believed in market rigging and cynically manipulated the flawed rules governing California's electric utilities, to secure illegal profits.

Lay preached the gospel of free enterprise, but perfected rent seeking on a massive scale. Enron's collapse and his criminal trial leave little room for retrospective redemption.

Lovins

For certain observers, mere restructuring of the electric power industry in aid of perfected markets did not suffice. Amory Lovins, the book's sixth power broker and a profound critic of the established order, early on announced his opposition to Insull's centralized monopoly legacy, "run by a faraway bureaucratized technical elite" and prone to "malfunctions, mistake, and deliberate disruptions."

In a game-changing article in Foreign Affairs in 1976, Lovins proposed a radical reset, arguing for "soft technologies" of conservation, efficiency, renewable power, and distributed generation, long before these were mainstream concepts. A passionate advocate for non-nuclear renewable power, whose declining cost he said would enable it to reduce the primacy of fossil fuels, Lovins also foresaw the onset of coal-driven climate change years before it became a common concern.

He predicted a market-based solution based on smart-grid efficiency, improved technology, and cost-competitiveness, rather than a carbon tax or a global treaty. This placed him at odds with other students of climate change and energy executives such as Jim Rogers of Duke Energy, the book's seventh power broker.

Rogers

An adept business strategist, Rogers saw beyond the insular confines of a hidebound industry. He found himself, following a succession of corporate acquisitions, at the helm of the nation's largest electric utility. Foreseeing that by mid-century "virtually every power plant in this country will be retired or replaced," Rogers sought a transitional political accommodation to protect his company and its customers from stroke-of-the-pen regulation.

He bargained intensely for an outcome acceptable to investor-owned utilities, but still played a critical role in support of federal carbon dioxide cap-and-trade legislation, that ultimately fell victim to partisan politics. Like founding father James Madison, Rogers feared "sudden changes and legislative interferences." He sought to moderate and anticipate change but believed Congress would ultimately have to alter the economics of coal-fired electricity. He tried to manage interferences at least cost, as he moved the industry toward an uncertain decarbonized future shaped by government action.

As my book reveals, the electric power industry has proved attractive to smart hyper-ambitious players seeking a platform to control people, institutions, and markets. Marked by technical complexity and economies of scale, the electric utility industry has typically treated regulatory change, or its prospect, as an opportunity to preserve or secure a dominant position. The tidal wave of change now engulfing Insull's industry requires an extraordinary strategic response and recognition of the government's pervasive role in driving a green industrial revolution.