Answers to questions you were afraid to ask

Chris Vlahoplus and John Pang are Partners at ScottMadden, Inc. Paul Quinlan is Clean Tech Specialist at ScottMadden, Inc. John Sterling is Senior Director, Research & Advisory Services at the Solar Electric Power Association.

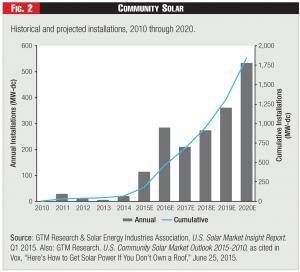

The topic of community solar is suddenly popping up everywhere. Annual installations are expected to jump five-fold-from 21 MW-dc in 2014 to 115 MW-dc in 2015.1 With this rapid growth, you may be wondering what exactly is community solar and how precisely do these programs work? This article offers answers to the burning questions you have been too afraid to ask your colleagues. Topics include key community solar drivers, program design features, and steps for electric utilities interested in designing a program. Let's jump in and get started.

How would you define this market segment called community solar?

While there is no standard industry definition, a community solar project is often characterized by multiple end users or subscribers procuring a portion of the electricity generated from a photovoltaic (PV) solar facility. Subscribers typically purchase a fixed kWh block of electricity or the actual, varying generation associated with a block of purchased capacity (kW). The solar project typically is located near the end-use customers, or at least within the energy provider's jurisdiction. Customers receive the benefit of the transaction on their electric bills. The term community solar does not apply to solar investments that provide a return or benefit outside of the electric bill.

What are the advantages of community solar?

Before discussing the unique advantages of community solar, let's first compare them to the benefits and challenges associated with two other solar market segments that also are growing: 1) residential rooftop solar and 2) utility-scale solar.

The primary benefit of residential rooftop solar comes from providing customers with locally sited renewable energy as an alternative to grid-supplied electricity. Many customers value the independence of direct ownership and the financial benefits of directly offsetting retail rates. Residential rooftop solar can also provide system benefits (e.g., avoiding some new investment in transmission and distribution capacity), but such benefits are not calculated or monetized in most markets.

The downside of residential rooftop solar concerns system costs and customer access. First, the price per Watt for a residential rooftop solar system runs more than twice the price of a utility-scale system.2 As a result, residential rooftop solar produces the most expensive form of solar energy. Second, customer access is also an issue, as only a fraction of the nearly 120 million households in the United States can qualify as good candidates for residential rooftop solar (see Figure 1). Many individuals are excluded for a host of reasons, including lack of homeownership (e.g., renters), unfavorable net-metering policies, credit scores preventing financing or leasing, and lack of a suitable roof (e.g., orientation, shading). As a result, a significant segment of the residential customer base remains unable to install rooftop solar on premises as a renewable energy resource. Now consider the utility-scale market segment. It offers benefits akin to central-station generation, as electric utilities can site and design systems for optimal performance with connections to the transmission or distribution system. Moreover, utility-scale solar offers greater output and economies of scale. That gives utility-scale solar a significant cost advantage over residential rooftop solar. Customers also can take advantage of utility-scale solar resources without any complicated transactions or up-front costs. But utility-scale solar also comes with a key drawback: customers lose any direct, tangible connection to the renewable asset. Instead, the generation asset serves all customers in a manner similar to conventional central-station generation.

Figure 1 - Residential Solar: Limitations based on ownership, net-metering policies, creditworthiness, rooftop configuration, and market conditions.

Figure 1 - Residential Solar: Limitations based on ownership, net-metering policies, creditworthiness, rooftop configuration, and market conditions.

By contrast, the community solar model is unique because it draws upon the best elements of residential rooftop and utility-scale projects. Similar to the case with residential rooftop installations, community solar provides customers with an opportunity to interact directly with a known resource within their local communities. And with generation sited close to load, benefits accrue both to utilities and customers. Electric utilities receive system benefits from the implementation of distributed resources at scale. Customers enjoy the benefits of utility-scale operations: lower system costs, a simple transaction format, and universal customer access. As a result, the individual customer receives value unavailable from the residential rooftop market.

How large is the community solar market segment?

Community solar today represents a small but rapidly expanding market segment. Cumulative community solar capacity should more than double in 2015-increasing from 67 MW-dc to 182 MW-dc.3 By the end of 2020, GTM Research (Greentech Media) forecasts cumulative capacity as exceeding 1,800 MW-dc (see Figure 2). This projection includes a spike in installations in 2016 in order to qualify for the 30 percent federal investment tax credit.

Public policy plays a major role in pushing growth for community solar. While 20 states have or are enacting supportive policies, GTM Research anticipates that 80 percent of community solar activity will occur in just four states: California, Colorado, Massachusetts, and Minnesota.4 Legislation authorizing community solar gardens or community solar tariffs provides the key impetus in California, Colorado, and Minnesota. The model in Massachusetts is distinctly different, however. In this market, net-metering policies allow participating systems to allocate excess generation to one or more customers within a distribution company's service territory.

Why would an electric utility develop a community solar program?

Electric utilities typically pursue community solar as a way to meet customer demand for solar that will prove more economic for the subscriber and that will benefit the system and customer base as a whole. Community solar also marks an excellent opportunity for utilities to become more engaged with their customers. Customers are known to show great interest in solar. They exhibit a marked willingness to pay an initial premium over the prevailing retail price of electricity in return for paying fixed prices through a community solar program. That provides customers a long-term hedge against any increase in electricity prices. On the other hand, the utility may pursue community solar in order to encourage more cost-effective solar deployment and to better integrate these resources into the grid. Utilities find themselves in a unique position to gain, as community solar allows the utility both to integrate the project into its overall business processes, such as by deploying existing billing systems and online platforms, and to improve the customer experience at the same time, which can expand the pool of potential customers, even while lowering the cost of acquiring new ones.

What program designs are typical for community solar?

Figure 2 - Community Solar: Historical and projected installations, 2010 through 2020.

Figure 2 - Community Solar: Historical and projected installations, 2010 through 2020.

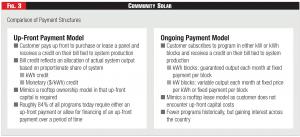

Here's another unique aspect of the community solar market segment: it offers an unlimited number of ways to design a program. However, within this context, two payment models have emerged as by far the most common. The first is the "Up-Front Payment Model." The second is the "Ongoing Payment Model."

In the Up-Front Payment Model, participating customers provide an up-front payment to purchase or lease panels or a specific nameplate capacity. As a result, this model mimics the initial capital cost of installing and owning a rooftop solar system. By contrast, the Ongoing Payment Model allows customers to make regular monthly payments to access solar capacity or output, typically via a utility rate schedule or rider. This second model mimics the regular payments and credits provided through third-party ownership of residential rooftop solar. Each payment structure is outlined in further detail in Figure 3.

The payment structure shown in Figure 3 marks just one of several key elements common to community solar programs. Also important is program administration, which can be managed by the electric utility or a third party. Additional design elements can include decisions for the following:

- Benefit structure

- Eligible customer classes

- Application or sign-up fee

- Treatment of renewable energy certificates

- Limits to program participation (e.g., percent of annual consumption)

- Production guarantees and risk

- Minimum participation term

- Overall program term

- Subscription transfers

- Unsubscribed energy

With so many design options, electric utilities or program administrators can fine-tune a community solar program to meet specific goals and objectives.

How would an electric utility develop a community solar program?

Figure 3 - Community Solar: Comparison of Payment Structures

Figure 3 - Community Solar: Comparison of Payment Structures

The lessons learned from early programs provide a clear framework to follow for an electric utility interested in community solar. Effective community solar programs proceed through four stages during development and implementation:

- Stage 1: Identify clear program goals and conduct due diligence

- Stage 2: Select design options for the community solar program

- Stage 3: Identify marketing plan

- Stage 4: Monitor program satisfaction

Key actions within the program development and implementation process are outlined in Figure 4.

Lastly, what trends have emerged for community solar?

In a recent survey of community solar programs,5 the Solar Electric Power Association (SEPA) found program development - defined as the time it takes from the initial decision to completion of a community solar project capable of producing electricity - takes an average of 10 months. The development time for smaller community solar projects, defined as less than 1 MW of capacity, is an average of 8.5 months. For larger projects above 1 MW in capacity, average is 13.4 months.

Once a community solar program is active, it's time to solicit customer participation. On this point, the SEPA survey found the average subscription rate to be 70 percent of available capacity (however a wide variation was observed within the reporting sample). Among fully subscribed programs, it took an average of six months to reach a 100 percent subscription rate. SEPA also compared subscription rates for programs relying o n the ongoing payment versus up-front payment models. No statistical differences were found in subscription rates between these two models. In addition, subscription rates were not impacted by other design elements, including length of program, financial payback, program size, customer cost, and marketing budgets.

Figure 4 - Community Solar: Program development and implementation process.

Figure 4 - Community Solar: Program development and implementation process.

Looking to the future, two-thirds of utilities surveyed report plans to expand community solar capacity in order to keep pace with growing demand. In addition, more than 50 utilities have announced plans to launch community solar programs in the upcoming 12 months. These planned programs promise a cumulative capacity of more than 200 MW-more than double the current cumulative capacity.

Endnotes:

1. Greentech Media, "U.S. Community Solar Market to Grow Fivefold in 2015, Top 500MW in 2020," June 23, 2015.

2. GTM Research & Solar Energy Industries Asso., U.S. Solar Market Insight Report. Q2 2015.

3. GTM Research & Solar Energy Industries Association, U.S. Solar Market Insight Report. Q1 2015.

4. Greentech Media, "U.S. Community Solar Market to Grow Fivefold in 2015, Top 500 MW in 2020," June 23, 2015.

5. Survey data in this section is from Solar Electric Power Association, Community Solar Program Design Model. November 2015.

Lead image © Uptall | Dreamstime.com - Detail Of Solar Panel Photo